World’s biggest trade deal in trouble over EU anger at Brazil deforestation

- The EU-Mercosur free trade agreement, finalized a year ago has been facing opposition from the EU after Brazil's destructive environmental policies and its failure to respect the Paris Climate Agreement.

- The trade agreement between the European Union and Mercosur (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay), is the biggest trade treaty ever negotiated. Signed a year ago, the US$19 trillion deal’s ratification could fail due to Brazil’s refusal to respond.

- At the end of June, French President Emmanuel Macron declared that his nation will not make “any trade agreement with countries that do not respect the Paris [Climate] Agreement,” a direct reference to the administration of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro who has pursued an aggressive policy to develop the Amazon.

- The Dutch parliament, Austria, Belgium, Ireland and Luxembourg, plus some EU parliamentarians, and NGOs are opposed to the deal, saying it brings unfair competition to EU farmers and accelerates Amazon deforestation. French and Brazilian business interests and diplomats meet this week to try and settle differences.

- Brazil’s Bolsonaro has so far been unmoved by all these objections. While the government plans to launch a PR campaign to convince the EU to ratify the trade agreement, it continues pressing forward with plans to allow industrial mining and agribusiness intrusion into Amazon indigenous reserves and conserved areas.

The European Union-Mercosur free trade agreement, finalized one year ago last June, faces growing opposition from European national governments, EU parliamentarians, and non-profit organizations, in addition to Latin American entities, putting its ratification at risk.

At the heart of this resistance: the EU’s strong dissatisfaction over Brazil’s destructive environmental policies and rapidly rising deforestation rate under President Jair Bolsonaro.

One of the biggest opponents of the trade agreement to date is the French government of Emmanuel Macron, whose party failed to triumph in municipal elections against the victorious Green Party on June 28, 2020. A day later, Macron suspended negotiations with the EU-Mercosur bloc. “[We will not make] any trade agreement with countries that do not respect the Paris Agreement,” said Macron, a clear reference to Bolsonaro and the Brazilian government.

The French president also urged the creation of the crime of ecocide, a crime against the environment, which should be judged by the International Criminal Court.

Fearful of Macron’s stance, French and Brazilian businessmen (particularly Brazilian agribusiness interests) are pressuring their respective governments to ease tensions between the two countries in favor of the Mercosur-EU trade agreement. Diplomats from both countries will participate in a video conference tomorrow, Tuesday, when they will review their bilateral agenda.

France is one of the largest international investors in Brazil. In 2018, the Banque de France, France’s central bank, revealed that French companies had 23.7 billion euros invested in Brazil, according to Valor Econômico.

If approved, the EU-Mercusor treaty — the biggest such global agreement ever negotiated — will create an open market encompassing 780 million people with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$19 trillion between the two blocs. The pact is of great value to both parties: EU countries will see most export tariffs to Mercosur eliminated, including for automobiles and chemicals; while the South American bloc, comprising Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay, will win exemption from import taxes on 81.7% of agricultural products.

In the Brazilian case, orange juice, fruits and vegetable oils, among other commodities, will have their customs duties eliminated, while beef, pork and poultry, in addition to sugar and ethanol, will be entitled to preferential access to the European consumer market through quotas.

When the agreement was signed last year, Brazilian Agriculture Minister Tereza Cristina declared that it would promote the modernization of the country’s agribusiness sector: “[It is] our products being sold to this market of more than 700 million people; I think it is a great opportunity.”

However, the signed, but not yet ratified treaty, quickly came under attack as President Bolsonaro aggressively dismantled Brazilian environmental protections. Environmental and human rights NGOs, along with protectionist interests among European producers and their lobbies, put pressure on EU national governments to reconsider the deal.

Opposition to the agreement grows

France isn’t alone in its opposition. The Dutch parliament has passed a motion against the EU-Mercosur trade deal on the grounds that it could bring unfair competition to European farmers and accelerate Amazon deforestation — the same objections have been raised by the governments of Austria, Belgium (the Walonia region), Ireland and Luxembourg, as well as by dozens of European parliamentarians.

Critical pressure increased last week when 265 European and Latin American organizations sent a letter to German Chancellor Angela Merkel and to the 28 EU member-states asking them to reject the Mercosur agreement. Last month, Client Earth and the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH), among other non-profit entities, filed a formal complaint with the European Commission for the treaty to be suspended.

The organizations condemn the Bolsonaro government stance on environmental and human rights, and argue that the trade agreement will worsen environmental destruction and the climate crisis with the dramatic expansion of commodities monocultures, including soy production, in the Amazon forest.

Delivered to the EU’s ombudsman — a channel through which civil society can question the functioning of the European Commission — the document asserts that the EU’s executive body signed the agreement without having carried out a full assessment on its future environmental impacts.

“The European Commission has ignored its legal obligation to ensure [that] the trade agreement with the Mercosur group of South American countries will not lead to social, economic, environmental degradation and human rights violations,” says the letter.

When the agreement was signed in the summer of 2019, the European Commission had not yet completed the final Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) report on Mercosur’s environmental performance.

Finally published last February, the SIA “does not include recent data on the rate of deforestation in Brazil, as well as recent information on changes made to its legal forest structure,” said Client Earth and its partner entities. If the EU ombudsman agrees to open an inquiry, the European Commission will have three months to respond.

The concern over deforestation

The treaty-building process has been highly intricate and fraught with challenges; the deal’s negotiation has already required 20 years. The legal text of the agreement is still not ready and, once finalized, will need to be translated into the 24 official languages of the European Union. Only then will members of the European Parliament be able to vote on the economic and commercial portions of the treaty. The political part, which involves topics such as the environment and human rights, needs to be approved by each of the 28 parliaments of EU member nations.

“At first, the pact, which is an Association Agreement [composed of commercial, political and cooperation pillars], needs ratification by the countries to come fully into force. If the European Commission, however, with the support of the European Parliament and its member states, separate the free trade agreement from the Association Agreement, they can try to implement its commercial part and leave aside the political issues of the pact, which include the environment — that is, provisionally implementing the agreement. Everything depends on what the European Commission will propose to the Parliament,” said Filipe Gruppelli Carvalho, an analyst at Eurasia Group, a U.S. political risk analysis consultancy with offices in five countries, including Brazil.

According to a recent Eurasia report, “If deforestation in the Amazon subsides, which is unlikely, and there’s no meaningful deviation from Brazil’s [Paris Agreement] climate commitments, Germany is likely to use its clout and backchannel negotiations to secure support for the pact from France and other sceptics.”

Although Germany is one of the biggest supporters of the trade agreement, Georg Witschel, who is leaving his post as ambassador to Brazil and returning to Berlin, declared in June: “Our government knows that securing a majority in our Congress and in the European Parliament is increasingly difficult with the deforestation growing in Brazil.”

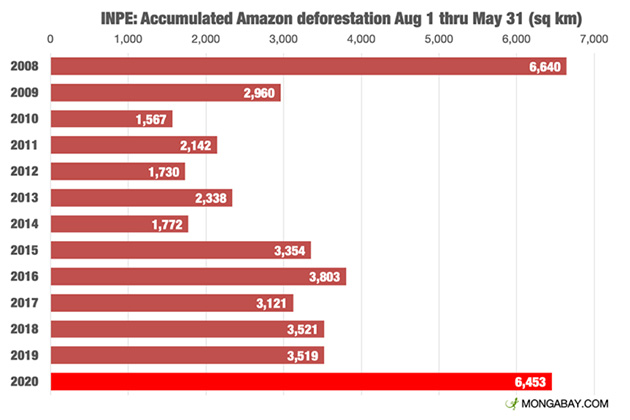

The Brazilian Amazon — the Earth’s largest rainforest — has seen 14 straight months of rising deforestation since Bolsonaro took office. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is currently pacing 83% ahead of where it was a year ago, and has reached levels not seen since 2008.

All eyes this year on upcoming Amazon fires

Carvalho, of the Eurasia Group, pointed out another important factor likely to enter treaty discussions in coming months: “EU technicians, bureaucrats and politicians will closely monitor what will happen in the Amazon during the dry season, which has just begun. Depending on the news, tempers will intensify against the agreement.”

Brazil’s national space research institute (INPE), recently reported that June 2019 saw 2,248 fire hotspots in the Amazon last June. The fires were mainly concentrated in Mato Grosso and Pará, states that led the deforestation ranking in 2018/2019. Most Amazon forest fires are not natural, but lit by people as a means of expanding croplands and pastures.

“Fires are associated with deforestation. In order to reduce their number, we have to reduce the deforested area. What we have seen is just the opposite [under Bolsonaro]. Deforestation is increasing every month compared to last year, when it went up very much compared to previous years,” said Ane Alencar, science director of IPAM, the Institute for Environmental Research in the Amazon.

Bolsonaro’s response so far: an advertising campaign to be launched in Europe to counter the environmental concerns of consumers and politicians. The administration has otherwise showed no sign of backing away from its policies of environmental deregulation and agency defunding. Last April, for example, Environment Minister Ricardo Salles declared in a meeting of ministers that the Covid-19 pandemic offered the ideal opportunity to “let the cattle pass,” distracting people from the government’s overturning of socio-environmental regulations.

Salles also recently appointed a business executive with no environmental experience — whose assets have been frozen since 2014 by the courts due to alleged administrative misconduct — to head the IBAMA office in Santa Catarina state (IBAMA is the nation’s environmental agency).

In another missed opportunity to curb the current rise in forest destruction, the Ministry of Agriculture (MAPA), whose sector is closely linked to escalating climate change, launched its 2020-2027 Strategic Plan, which presents the ministry’s strategies for that period.

According to Tasso Azevedo, a forest engineer and coordinator of the non-profit Climate Observatory’s Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimation System (SEEG), the new MAPA plan “disregards or barely touches on the main challenges facing agricultural production, such as coping with climate change and conservation of soil and water… But the most incredible thing is the total absence of any reference to deforestation.” The agriculture plan, experts say, does not bode well for EU-Mercusor trade agreement ratification.

“More than 95 percent of the deforested areas in Brazil are occupied by agricultural activities (and more than 99 percent of the deforestation has strong evidence of illegality). Agriculture is thus [mainly] responsible for, or the direct beneficiary of deforestation” said Azevedo. “The MAPA plan ignores the need to disconnect Brazilian agribusiness from deforestation by the concrete reduction of forest clearing rates and the implementation of a robust production traceability program. Instead, it promises a communication program to contain negative news about Brazil.”

Contacted by Mongabay, MAPA replied that “it is not responsible for fighting deforestation, a role that falls to the Ministry of the Environment. As much as the [deforestation] agenda is relevant and the federal government, especially with the structuring of the Amazon Council, is acting to curb illegal deforestation, it would be a mistake to include in the Strategic Plan of the Agriculture Ministry a matter that is not within its competence.” Critics argue that the newly formed Amazon Council is intended as an end run around the past enforcement role of IBAMA.

MAPA added: “It is up to this ministry to work for the environmental damage mitigation caused by agricultural activity through public policies that ensure that Brazilian agriculture continues to grow through productivity, with innovation and efficiency, as well as through the environmental regularization of rural properties in accordance with the Forest Code, land tenure regularization, and the socioeconomic development of producers. Such elements contribute directly to the reduction of illegalities in deforestation and other illegal or non-recommended practices of natural resources.” Analysts say that the major 2018 revision of Brazil’s Forest Code put vast areas of protected Amazon forest at risk.

The outcome of the standoff between Brazil’s Bolsonaro — dedicated to commodities growth at all cost — and the environmentally sensitive EU, remains uncertain. But many analysts say ratification of the trade deal, if it happens at all, will require complex maneuvering and concessions. Ratification is expected at the earliest sometime in 2021, though it may take far longer. And the whole deal could all go up in smoke if this year’s Amazon fires in August and September greatly surpass those of 2019.

This article first appeared on Mongabay.