That coconut oil you love? Species have gone extinct over it. True story

- As per recent study, palm oil may not be the only consumable oil that causes destruction to biodiversity. We know little about the environmental footprint of other consumable oil crops.

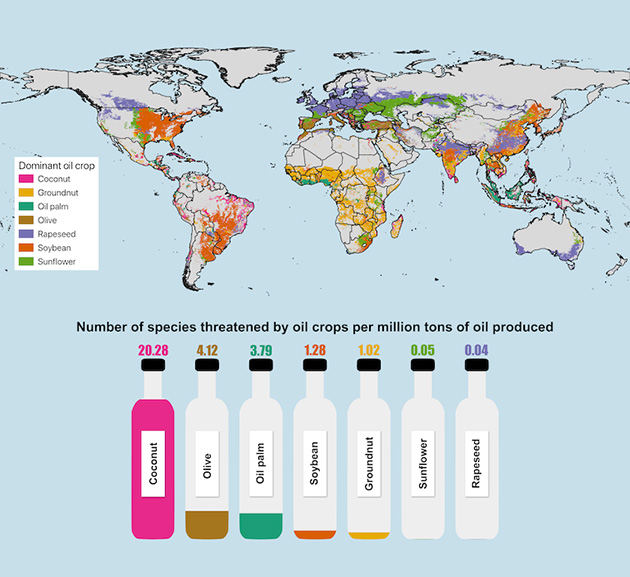

- A new study found that coconut oil production, by some measures, is more destructive than palm oil production, with coconuts affecting 20 threatened species per million liters of oil produced, and palm oil only affecting 3.8 species per million liters.

- Globally, coconut farms occupy 12.3 million hectares (30.4 million acres) of land, about two-thirds the area of oil palm plantations, with most farms located in Indonesia and the Philippines.

- Instead of positioning coconut oil as a product that should be avoided, the study aims to demonstrate that most consumable oils, such as olive, soy and rapeseed oil, have a negative impact on the environment, although these impacts are not all well known or publicized.

For conscious consumers, palm oil tends to be the pariah of tropically grown crops. This is due to the well-publicized fact that oil palm plantations are highly destructive to biodiversity, displacing critically endangered species like orangutans. But palm oil isn’t the only consumable oil that causes environmental damage, according to a new study. It argues that the public is grossly uninformed, or even misled, about the environmental footprint of most oil crops. To illustrate this point, the authors put the spotlight on the popular husk-covered seed with its fleshy, milky center: the coconut.

According to the study, published in Current Biology, the production of coconut oil impacts 20 threatened species per million liters of oil produced. By this measure, coconut oil is positioned to be more destructive than palm oil, which only affects 3.8 species per million liters, or even soybean oil, which impacts 1.3 species per million liters. However, few people know this, Erik Meijaard, the study’s lead author, told Mongabay.

“[There’s a] discrepancy between what people think because of their cultural biases and lack of understanding or knowledge, and what the reality tells us,” Meijaard said. “Because if you’re missing part of the picture that, in this case, [is] the fact that coconut is actually problematic for biodiversity … then no one is going to address that, and we don’t solve the problem.”

Meijaard, who is the director of Borneo Futures, a scientific consultancy based in Brunei Darussalam, and has worked in tropical conservation for 28 years, says he’s always wondered why conservationists and consumers loathed oil palms, but not coconut palms. “Both of them are tropical plants that are occupying large areas that previously would have been covered in natural forest,” he said. “Why does one end up being evil and the other one being wonderful?”

But it wasn’t until Meijaard and his colleagues started working on this paper, which used data from the IUCN’s Red List, that Meijaard said he came to understand the true impacts of coconut oil as well as other oil crops on biodiversity. The results of the study, Meijaard says, came as a “surprise.”

Coconuts are grown in many parts of the world, but the majority of production takes place on smallholder farms in Indonesia and the Philippines, where “species endemism and richness typically exceed those of mainland nations by a factor of 9.5 and 8.1 for plants and vertebrates,” according to the study. On a global level, coconut farms actually take up less space than other oil crops: 12.3 million hectares (30.4 million acres) for coconut palms compared to about 18.9 million hectares (46.7 million acres) for oil palms. Yet coconut plantations affect 66 species listed on the IUCN’s Red List, including 29 vertebrates, seven arthropods, two mollusks, and 28 plants, the study says.

For instance, it’s believed that coconuts farms were responsible for the extinction of the Marianne white-eye (Zosterops semiflavus), a tiny bird from the Seychelles, and the demise of the Ontong Java flying fox (Pteropus howensis) on the Solomon Islands, a species that hasn’t been seen for the last 42 years and is feared to be extinct. Other species threatened by coconut production are the endangered Sangihe tarsier (Tarsius sangirensis), a small primate endemic to the Indonesian island of Sangihe, and the endangered Balabac mouse-deer (Tragulus nigricans), an animal found on three Philippine islands.

Meijaard says that coconut oil shouldn’t necessarily be vilified, but that consumers need to arm themselves with information.

“We want to be very careful not to say that coconut is actually a greater problem than palm oil,” Meijaard said. “What we’re really trying to say, and trying to get the public to understand, is that all agricultural commodities have their own issues.”

While this study focuses on coconut, it points out that other oil crops, such as olive, soy and rapeseed, have serious environmental issues attached to them. For instance, it references a piece in Nature that says high-powered machines used to harvest olives kill 2.6 million birds each year in Spanish Andalucía.

“The production of olive oil, however, rarely raises concerns among consumers and environmentalists,” Meijaard and his co-authors wrote in their study. “There are various perceptions at play — the olive oil industry benefits from the belief that it represents a sustainable practice with an extensive heritage and mythology, claims of health benefits and being locally based. Conservation thus often appears to be impaired by shortsightedness and double standards, frequently driven by environmental campaign agendas.”

“Consumers need to realize that all our agricultural commodities, and not just tropical crops, have negative environmental impacts,” Douglas Sheil, co-author of the study in Current Biology, and professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, said in a statement. “We need to provide consumers with sound information to guide their choices.”

Meijaard said he hopes that the study encourages further research on the environmental impacts of oil crops, so that the public can become better informed about their product consumption.

“At the moment, we’re simply not there yet,” Meijaard said. “We can pick any crop, and there are huge holes in our understanding and knowledge about their impact, so it’s a call from us for scientists, politicians, and the public to demand better information about commodities.”

This article first appeared on Mongabay.