Snow leopard conservation handicapped by lack of research

- As climate change exacerbates the threats faced by the species, researchers say study of snow leopards must be ramped up and diversified to secure the health of Asia’s mountain ecosystems

More than 70% of snow leopard habitat remains understudied by conservationists, leaving conservation planning handicapped by large information gaps, according to a recent report by WWF.

Snow leopards live across the cold and rugged high mountains of Asia, from Pakistan, India, Nepal and Bhutan, through China and Central Asia to Russia and Mongolia. In this landscape spanning approximately 1.8 million square kilometres, there are estimated to be fewer than 6,400 snow leopards. Another estimate by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) puts the global population between 2,710 and 3,386 adult snow leopards.

Healthy populations of top predators play a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem health, including by keeping herbivore populations in check, thereby securing local vegetation. The mountains where snow leopards live also form the headwaters of 20 major river basins, a crucial water source for the more than two billion people across 22 countries who live in the basins of these rivers.

The WWF report is based on a systematic review of snow leopard research spanning 100 years up to 2020. The idea behind the report was “to figure out whether we have adequate information on snow leopards to determine what the conservation action should be,” said Rishi Sharma, one of the authors and lead of the snow leopard programme at WWF.

The findings point to a lack of information from large portions of the snow leopard’s range. “This is worrying. This is what conservation organisations and governments should be focusing on,” said Sharma.

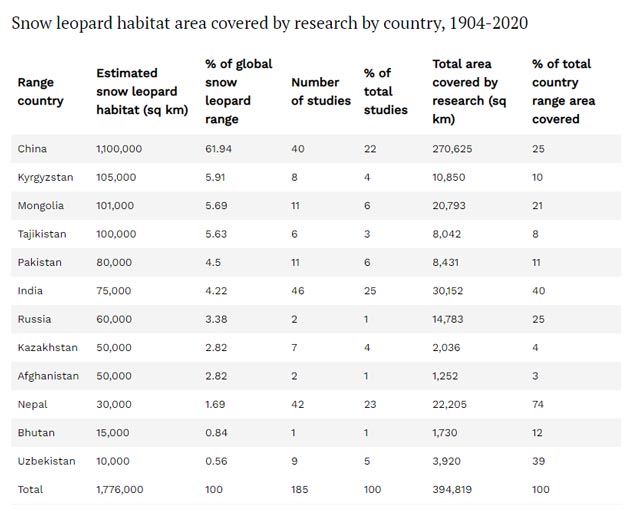

The report shows that Nepal and India are leading snow leopard research, followed by China. There are huge research gaps in Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Bhutan, Russia and Pakistan.

“We have tagged snow leopards that have gone to Afghanistan from Pakistan but because there’s no research going on [in Afghanistan], we have no idea at all how many [snow leopards] there are,” said Rab Nawaz, senior director of programmes at WWF-Pakistan.

Inaccessible mountain terrain a challenge for researchers

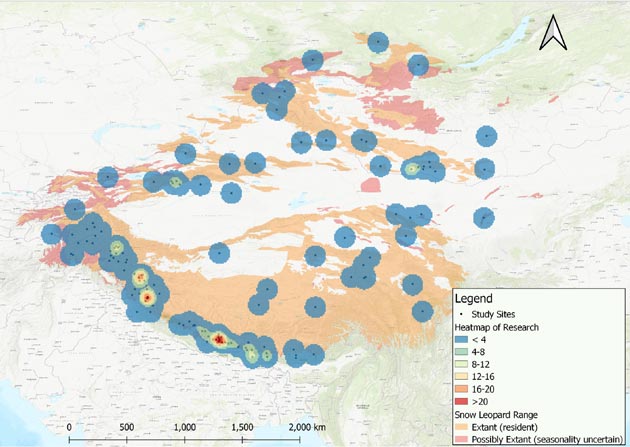

Nawaz said that research on snow leopards in Pakistan is “very concentrated in very few areas” like Chitral National Park in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Valleys on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border that are very likely home to snow leopards have not been studied because they are difficult to access.

The tough terrain and harsh climate of much snow leopard habitat makes research particularly demanding, a primary reason why vast sections of snow leopard habitat remain uncharted territory for researchers.

“Access to some of these areas is difficult and even if you manage [to access them], the logistical challenges of doing research come into play,” Rishi Sharma said. He compared his research experiences with tigers in central India with his work on snow leopards. “In central India, we could take a four-wheeler and cover substantial areas and install around 25-30 camera traps [in a single day]. In Spiti or Ladakh [in the north Indian Himalayas] or any other snow leopard range, even visiting three sites in a day is difficult.”

The report also points out that less than 3% of snow leopard range has robust data on snow leopard abundance, and that multi-year research is being carried out in only four research hotspots.

There is however space for hope. “The one positive thing I see is that there has been a huge increase in research in the last decade,” said Justine Shanti Alexander, regional ecologist at the Snow Leopard Trust and executive director of the Snow Leopard Network, who provided inputs for the WWF report.

Missing link: snow leopards and rangelands

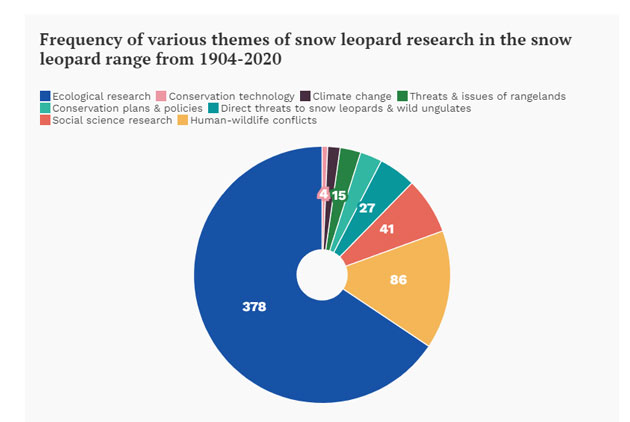

The WWF report points to glaring gaps in the human elements of snow leopard conservation in research to date. Rangeland-related issues are highlighted as one of the least studied aspects of snow leopard conservation, despite their importance.

Lands that make good snow leopard habitat are also often those where livestock herding is the dominant human activity. Meanwhile, only 14-19% of snow leopard range overlaps with protected areas. This means that herders and snow leopards largely live alongside each other, leading to potential for conflict which endangers both livestock and snow leopards. The WWF report states that between 221 and 450 snow leopards are killed by people every year, and that 55% of these killings are driven by retaliation for snow leopard predation on livestock.

221-450 snow leopards are killed by people every year

“What this means for conservation is that we should understand the human dimension of the story. What do people who live with snow leopards think? How is their life impacted by living with a predator which kills their livestock?” Rishi Sharma said. “In-depth research on the social science aspect of snow leopard conservation is lacking.”

A study published last month highlighted case studies from India, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Pakistan to show how “respectful engagement and negotiation” with local communities can go a long way in addressing human-wildlife conflict. Many conservation organisations, including the Snow Leopard Trust, Nature Conservation Foundation and WWF, are working to support communities in mitigating conflict. For example, there are efforts underway to reduce livestock loss by building predator-proof corrals and holding pens in the Spiti Valley in Himachal Pradesh and Changthang in Ladakh.

A major caveat is scale. “These efforts are limited in terms of their geographical coverage. So, unless [the issue of conflict] finds place in government policies, we will only find success in certain areas. The hard thing to do is replicate the success across larger areas of the snow leopard range,” Rishi Sharma explained.

Commercial livestock rearing – more capital-intensive and organised than traditional pastoralism – can also cause problems for snow leopards. A 2015 study found that livestock grazing and snow leopard habitat use are “compatible up to a certain threshold of livestock density, beyond which habitat use declines”. The reason for this, the authors said, is possibly due to “depressed wild ungulate abundance and associated anthropogenic disturbance.”

Rishi Sharma points out that production of pashmina is an important economic activity on parts of the Tibetan Plateau. “The challenge is, how do you reconcile wildlife conservation goals with government policies which aim to promote pashmina and when pashmina is also an important economic activity for the people.” According to Sharma, such economic incentives have led to a situation where “there is more livestock than what these rangelands can sustain.”

The growth of mining and infrastructure like roads and dams pose challenges for both snow leopards and rangelands. “In the last 10-15 years, demand for minerals has opened up remote pastures for mining in countries like Mongolia, China, Kyrgyzstan,” said Koustubh Sharma, assistant director of conservation policy and partnerships at the Snow Leopard Trust. In some areas, like Tost Nature Reserve in Mongolia, herder communities have viewed snow leopard conservation as a means to protect pasturelands from threats like mining. “The area has been declared as a protected area for [conserving] snow leopards, ibex and argali and there’s zoning to allow grazing,” said Justine Shanti Alexander.

Climate change impacts on snow leopard habitat

Only around 35% of current snow leopard range will remain climatically stable and suitable for viable snow leopard populations by the late 21st century, a 2016 study predicted. Despite such startling statistics, the WWF report highlights that climate change is a major unexplored theme in snow leopard research.

“We call climate change the mother of all threats because it amplifies each of the other threats that snow leopards face like retaliatory killing, poaching and extreme weather resulting in lack of prey,” said Koustubh Sharma. This makes these threats “much more severe and urgent and complex”.

Climate change is driving more frequent flash floods and dzuds (a Mongolian term for extreme winters), among other impacts. This can push people into hitherto unexplored areas, in search of better pastures for livestock or more comfortable conditions for living. “These new areas may be snow leopard habitat and [this] can lead to conflict,” said Koustubh Sharma.

The pressures of climate change can also make other conservation interventions more difficult. “It remains challenging to expect communities that are experiencing poverty and climate change-related shocks like drought to go beyond immediate mitigation of risks of carnivore depredation and take on additional broader actions related to snow leopard conservation,” said Alexander. She added that working with communities to build resilience against environmental shocks is important for long-term conservation of high mountain ecosystems.

“As of now, the immediate climate change-related threat is… how people [living with snow leopards] respond to climate change,” said Koustubh Sharma.

The path ahead – landscape-level conservation

In 2013, the governments of all 12 snow leopard range countries adopted the Bishkek Declaration with a shared goal of conserving snow leopards across their habitat. The Declaration lays out steps countries should be taking towards conserving snow leopards over the long term through the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Programme (GSLEP).

“Under GSLEP, all 12 countries recognise that landscape-level conservation [rather than country-level ones] are needed,” said Koustubh Sharma.

Alexander highlighted the importance of “secured and connected” habitats for snow leopards. In China, predicted to host 50-60% of the world’s total suitable snow leopard habitat, large areas are protected as nature reserves. For instance, Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve, at more than 150,000 square kilometres, is more than half the size of Kyrgyzstan. “This is vital because snow leopards have large home ranges and to protect a population you need at least several thousand square kilometres,” Alexander added.

Recognising landscape-level issues also means acknowledging that the landscape is used in multiple ways. “The best way to conserve snow leopards is to partner with local communities, minimise the losses they face and maximise the benefits they can gain from the fact that they share snow leopard habitats,” said Koustubh Sharma.

This article was first posted on The Third Pole.

This work is under Creative Commons’ Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 England & Wales License.