Indian grasslands hold a treasure trove of endemic plants

- Indian savannahs contain 206 endemic plant species, of which 43% were described in the last two decades. More endemic species are waiting to be discovered, underscores a new study.

- The grasslands of Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats are hotspots for the discovery of endemic plant species.

- Grasslands are equally important as forests in biodiversity conservation and climate mitigation goals, say experts.

Indian savannahs, often tagged as ‘degraded forests’ in the afforestation framework, are likely to throw up “tons of new plant species,” say Indian scientists in a new study.

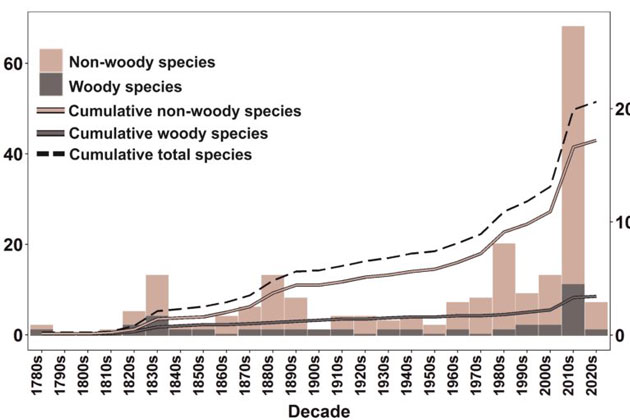

Scouring through taxonomic records from the 1780s to September 2020, the scientists found that the Indian peninsular savannahs, or grassland ecosystems, contain 206 endemic plant species, of which 43% were described in the last two decades (post-2000). Before the rapid increase in discoveries post-2000, the 1830s, 1880s and 1980s show three smaller discovery peaks.

“There were 68 species described in the 2010-2020 decade alone, and if you look at our data, the trend is an exponential rise in the discoveries, which means several more species remain unknown to science, scientists and conservation biologists,” said the study’s corresponding author Ashish N. Nerlekar at the Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA.

The authors, while expecting an increase, were surprised by the exponential rise in species discovery over the years. They emphasised the need to invest in training more botanists, prioritising hotspots for biodiversity surveys and managing savannahs to support endemic species diversity.

The records analysed in the study spanned grasslands in Rajkot in Gujarat to Pune and Nannaj in Maharashtra and Mahakuta in Karnataka to the Eastern Ghats and the Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh. Some of the most prominent endemic species that the grasslands harbour are Crotalaria shrirangiana (Fabaceae), Tephrosia calophylla (Fabaceae) Brachystelma penchalakonense (Apocynaceae) and Brachystelma gondwanense (Apocynaceae).

“The goals of the Convention on Biological Diversity will only be met if we accelerate the discovery of missing species before they go extinct. Since how many endemic species are there in a given region, is a basic metric for deciding conservation interventions and priorities, our study helps provide the first estimate for these savannahs at a large scale,” Nerlekar added.

According to the analysis, the eastern edge of the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats mountains are the two hotspots for plant discoveries, and future discoveries are most likely to be of plants that are short-statured and rare which is in line with discoveries in other groups like butterflies.

Nerlekar expanded, “Biologists tend to come across larger and more common species first than smaller/inconspicuous and rare species. This is actually a very intuitive reason for the patterns of plant and animal discoveries in many parts of the world. Once the most common and apparent species are described, it’s much harder to look for smaller and rarer species.”

It’s no surprise that mountains contain hotspots for encountering new species. Mountains support a diversity of climates, microclimates and habitats and microhabitats in these mountains are an ideal opportunity for speciation and maintaining endemic diversity. The evolution of endemic species in India’s grasslands also reflects the region’s paleohistory, researchers said.

India, after it separated from the supercontinent of Gondwana, passed through various paleoclimatic belts crossing through equatorial climate, experiencing the evolution of diverse plant communities including ancestral plant forms of the present-day plant communities.

One example is Glossopteris, extinct seed ferns which are primitive plant forms of present-day seed-bearing plants, observed study co-author R. Ganesan. “As part of evolution following the climate belts through which while the Indian plate was rafting, diverse plant communities kept changing their range of distribution and population size. During tectonic plate movement, many plants have gone extinct; and also the same process that is reasoned for extinction also facilitated the origin of new taxa,” Ganesan at Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), told Mongabay-India.

Rainforest habitats transformed into salt marshes or deserts and ice-covered mountains were subsequently enveloped by wet forests. Some plants escaped these changes by taking refuge in mountains or valleys and spreading and evolving when favorable climate prevailed. The aridity and ice age shaped life on earth and the evidence is chronicled in the form of coal beds or fossil forms, not only in the Indian sub-continent but also globally, narrated Ganesan.

The evolution of endemic plants in the aridity of the savannah biome can be traced in the plant biodiversity of peninsular India, with the Eastern and Western Ghats and the Deccan Plateau. “These savannah biomes of India are also the cradle for the evolution of diverse crop plants following human footprints,” he said.

Botanist Anzar Khuroo, who was not associated with the research, says the study has implications for the conservation of biodiversity and for climate mitigation-associated policies and programs that tend to focus mostly on trees. “Don’t take only the forests as the green campaign or for the conservation of biodiversity. It is the mosaic of ecosystems that is important. There are many open types of landscapes that are equally important to biodiversity and this study has helped a lot in bringing that point home.”

“These grasslands, which are often termed as ‘wastelands’ are equally important as forests when we talk about mitigating climate change, conservation of biodiversity and sustainable development,” Khuroo told Mongabay-India. “Tomorrow if we have developmental projects in these open-type landscapes there would be no public outcry because they do not occupy the same space in the public consciousness as forests do,” he cautioned. Khuroo expects similar results from Himalayan meadows.

The study authors bat for making savannahs a conservation priority like forests.

“Most existing conservation prioritisation activities and analyses have used endemism as a proxy for identifying high conservation priority areas. Since the savannahs were always assumed to be landscapes devoid of endemics, they have always been an ignored conservation priority as opposed to forests. Our data now shows that there is considerable endemism in these savannahs as well and conservation priorities must now be re-align to protect both forests and savannahs,” said Ashish Nerlekar.

Training more and better botanists would augment the “uphill task” for botanists to trace the missing species since future plant discoveries are expected to be of small-statured and range-restricted plants.

“With limited resources allocated to field biology and taxonomy, if one were to prioritise areas given such funding constraints, focusing on the two hotspots (Eastern Ghats and the Western Ghats) might be a desirable option,” Nerlekar said.

The authors also called for managing savannahs in a way that sustains endemic diversity.

“Several of the endemic plants we list show traits that are known to be fire and grazing adaptations (e.g. presence of below-ground bud banks, fire stimulated germination, etc). These adaptations, along with other lines of evidence (e.g. fossil pollen data) clearly show that fire and grazing have historically been an important driver maintaining and shaping endemic plant diversity. Unfortunately, fire and grazing are perceived as degrading forces even by botanists, with little empirical evidence to back up such claims, and on this backdrop, we recommend that Indian savannahs be managed in a way that best mimics the historical grazing and fire regimes,” Nerlekar said.

“Managing savannahs as savannahs is also an important implication of our study rather than undertaking misplaced afforestation drives that consider them as ‘degraded forests’ and aim to ‘restore’ these naturally open-canopy landscapes to a forest state,” he added.

CITATION:

Nerlekar, A. N., Chorghe, A. R., Dalavi, J. V., Kusom, R. K., Karuppusamy, S., Kamath, V., Pokar, R., Ganesan. R., Sardesai, MM & Kambale, S. S. (2022). Exponential rise in the discovery of endemic plants underscores the need to conserve the Indian savannas. Biotropica.

This article first appeared on Mongabay.