Droughts and late monsoon floods batter South Asia

- Intensifying climate change means that opposite disasters are manifesting at the same time across the region, making emergency responses harder than ever

As many parts of India, Nepal and Bangladesh face floods, drought continues to affect large swathes of Pakistan and some areas of India. In a cruel irony, parts of India that were hit by drought until the end of August are now expected to be flooded mere weeks later. Last month, the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reconfirmed that such erratic weather patterns, tied to an increasingly unpredictable monsoon cycle, bear the hallmark of climate change.

India’s latest flood situation report, published on 14 September and compiled by the non-profit Sphere India, counts over 3.8 million people affected over eight states. Eight people have died and 11,769 are in 142 relief camps, while 322 houses have been damaged.

Nepal’s capital Kathmandu received 121.5 millimetres of rainfall on 7 September – the fourth-highest 24-hour deluge on record, and third-highest in the past two decades. The Bagmati River that winds through the city burst its banks. According to police reports, around 150 people had to be rescued and over 400 houses were affected.

In Bangladesh, flooding occurred in both the Brahmaputra and Ganga basins, though water levels started receding by 11 September. In Rajbari district near the Padma River – the main distributary of the Ganga – children were forced out of flooded school buildings, while students in Tangail district had to row to school. Thousands of weavers fear financial ruin after their looms were flooded. The distress was particularly severe in the riverine islands, called chars, because after the Covid-19-induced lockdowns forced many people to move away from the capital Dhaka, their populations increased unexpectedly.

Severe droughts, despite monsoon revival

The drought in Pakistan eased a little after showers in the first half of September in the affected provinces, Sindh and Baluchistan. Water levels in reservoirs are still low.

India’s Drought Early Warning System (DEWS) shows pockets of drought persisting on 12 September in western Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Punjab – the breadbasket of the country – as well as in western Rajasthan. Groundwater irrigates most of the breadbasket, but crops now face damage, with the India Meteorological Department forecasting rainfall in this area as the 2021 monsoon persists.

On 24 August, DEWS data revealed 21.06% of India faced drought, up from 7.86% at the same time last year. Late monsoon rainfall has reduced this figure substantially, but that is of little solace to farmers who depend on monsoon rainfall – as they have lost the main sowing period of the year.

An unusual area of drought in 2021 is Nagaland in northeast India. Traditionally a heavy rainfall area, seven of the state’s 12 districts received rainfall below the long-period average by 21 August. The state now faces water scarcity and a poor harvest.

A deluge of disasters during 2021 monsoon

Throughout the 2021 monsoon, there have been so many cloudbursts in the Himalayas – with consequent flash floods and landslides – that it is difficult to keep count. There have been unprecedented landslides and flash floods in the Western Ghats of Maharashtra as well.

According to Nepal’s Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, three of the four heaviest recorded rainfall events in the Kathmandu valley have occurred in the past two decades. The authority says that this year, 115 people have already died due to floods and landslides, while 40 are missing and over 100 injured.

“With climate-related extremes on rise and encroachment of waterways, including by state, damage in the future is likely to be of colossal proportions,” tweeted Arun Bhakta Shrestha, manager of the river basins and cryosphere regional programme at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development.

In line with IPCC forecast

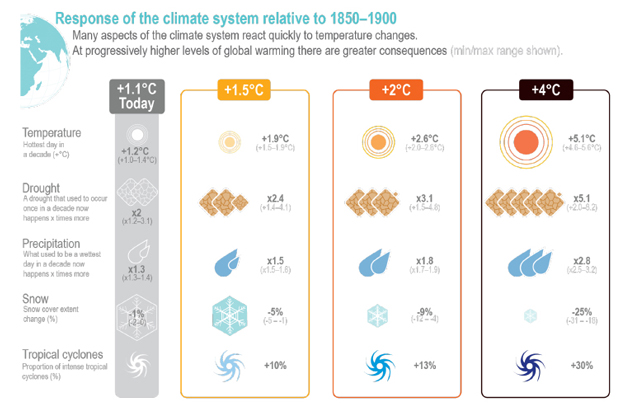

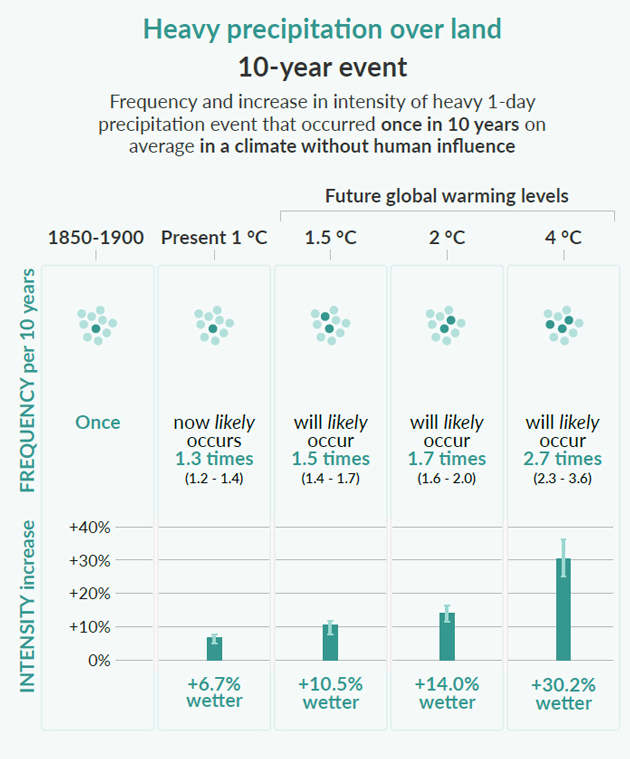

The highly erratic behaviour of the 2021 monsoon aligns with the latest findings and forecasts of the IPCC scientists. In their report released on 9 August, experts said that severe global precipitation events occur on average once every 10 years in a climate without human influence. They project these events will nearly double in frequency at 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. At 4C higher, the likelihood of these events will be 2.7 times higher. The new report concludes with high confidence that human-induced climate change is likely the main driver of both increasing hot extremes and heavy precipitation.

The main reason, the IPCC said, “is that continued global warming is projected to further intensify the global water cycle, including its variability, global monsoon precipitation and the severity of wet and dry events.”

On the South Asian monsoon, the scientists – who included experts from the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology – projected “an increase in annual mean precipitation. The increase in rainfall will be more severe over southern parts of India. On the southwest coast rainfall could increase by around 20%, relative to 1850-1900. If we warm by 4°C, India could see about a 40% increase in precipitation annually.”

Worsened by badly planned development

In the past four decades, Kathmandu’s built-up area has quadrupled, and buildings are encroaching on river floodplains. The water recharge capacity of the valley has decreased dramatically due to cementing of large areas. Experts have warned that effects of climate change such as extreme rainfall events, together with haphazard developmental activities at the cost of hydrological integrity, will make things worse.

“Flood risk reduction is more about drainage than control,” tweeted Ajaya Dixit, noted water expert and adviser to the Nepal branch of the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition. “Rivers must be given space. Tools are needed to address extreme events and understand them better. Focus should go toward interdisciplinary water education.”

This article was first posted on The Third Pole.

This work is under Creative Commons’ Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 England & Wales License.