As India breaks the taboo over sanitary pads, an environmental crisis mounts

- More young Indians are adopting safer menstrual practices, but polluting materials pose an environmental hazard that remains unaddressed.

In the throes of the first pandemic-induced lockdown in Indian history, many started to reflect on how humans’ footprint on the environment can eventually come back to bite. It was during that time that Delhi-based Simran Monga and her family decided to play their part and go zero-waste.

The Mongas measured their monthly domestic trash of almost 60 kilograms, ordered a terracotta compost unit, and started phasing out non-compostable items. But even after weeks of planning, one particular item proved a nut hard to crack: sanitary pads. “It’s a taboo subject, it’s a health requirement but let’s accept that it’s an environment polluter too,” said Simran, a 27-year-old graphic designer.

Simran is one of the 336 million menstruating people in India, of whom nearly 121 million use commercially produced disposable sanitary napkins, according to a study by WaterAid India and Menstrual Hygiene Alliance India. The study says that disposable sanitary pads may take over 500 years to decompose, posing a big environmental challenge.

What makes the problem more complex is that in developing countries like India menstrual health is not only a big hygiene issue, but also a social taboo. While a society cannot compromise on efforts to increase access to sanitary hygiene products in a country where women’s health is often neglected, the amount of steadily growing menstrual waste is an equally acute environmental issue, said Delhi-based waste management expert Swati Singh Sambyal.

“Disposable sanitary napkins are a hazard because 70-90% of a sanitary pad is made of plastic,” Sambyal said. One pad is equivalent to four plastic bags, “so one can imagine the quantity of single-use non-biodegradable plastic generated every month from sanitary napkins. It’s a strong enough issue to raise environmental concerns.”

Growing usage and market

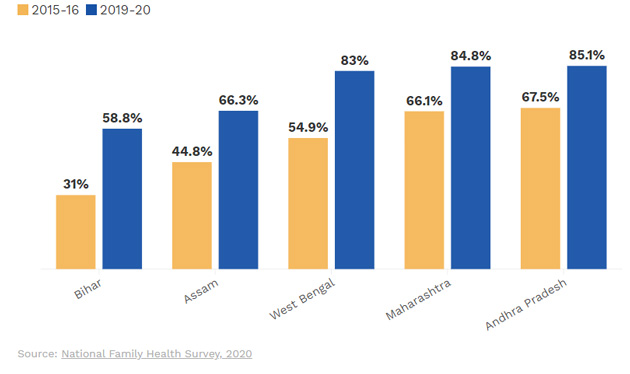

The latest government data show that adoption of sanitary pads is growing steadily among the 15-24 age group. For example, in Bihar 58.8% of girls and women in this age group were using such products, recording an almost 90% growth in four years. In Andhra Pradesh its usage has risen to 85.1% from 67.5% in 2015-16. A similar trend is observed in most Indian states.

Sanitary pad use is rising among young women in India

Use of “hygienic methods of protection during periods” by women aged 15-24

In 2020, the Indian sanitary napkin market touched USD 521.5 million and is expected to reach USD 975.4 million by 2026, according to US-based market research firm Expert Market Research (EMR). “Sanitary pads are now widely available, but are we meeting this greater availability with appropriate waste management solutions that do not harm users and the environment?” said Arundati Muralidharan, policy manager at WaterAid India and author of the charity’s 2018 report on menstrual waste.

Comfort and the pain points

Initially, sanitary napkins were made of cotton and gauze. But to opt for a more cost-effective raw material, manufacturers turned to wood pulp, an absorbent material. Then came the plastic revolution, which changed sanitary napkins’ composition – which is comfortable but not healthy, said Pooja Katkar, assistant professor at DKTE’s Textile and Engineering Institute in Maharashtra.

Now, the top permeable layer of the sanitary napkin is made of polypropylene or polyethylene. Inside fluffy pads the absorbent core is wood pulp, and in ultra-thin ones it is made of Super Absorbent Polymer (SAP). And the bottom barrier layer is made of polyethylene, explained Swati V Chavan, another assistant professor of textile chemistry at DKTE’s Textile and Engineering Institute.

These components might look innocuous, but essentially the majority of it is non-biodegradable, and bad for women’s health, according to Delhi-based gynaecologist Meenakshi Sahu. Plastic in sanitary pads “disturbs vaginal microflora balance and can cause health problems including urinary tract infection, rashes and genital tract infection,” Sahu said.

Policy gaps

While the waste pile is a practical and measurable problem, policies remain vague. India’s pollution watchdog the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCD) mandated that soiled napkins as well as other sanitary products should be separated into biodegradable and non-biodegradable components. However, the BioMedical Waste Management Rules 2016 indicate that items contaminated with blood and body fluids, including cotton, dressings, soiled plaster casts, lines and bedding, are bio-medical waste and should be incinerated, autoclaved or microwaved to destroy pathogens, according to the CPCB.

However, environmental experts, social enterprises and studies argue that when these pads are burned in the open or in incinerators, they release toxic chemicals such as furans, a highly volatile chemical compound, and dioxins that are known carcinogens.

Sambyal pointed out that commercial napkin brands add to the problem by not disclosing the product composition on the package, but Richa Singh, chief executive of sanitary napkin brand Niine said there is “no mandatory rule in India to mention the composition of their products on the packets”.

Green alternatives or greenwash?

Amid growing apprehension about sanitary pads’ environmental impacts, several social enterprises are now offering alternatives. Some are biodegradable and compostable, while others include reusable absorbent underwear, menstrual cups and reusable cloth pads – a modern and better-designed version of the traditional pad.

A 2020 study found that some 63% of Indian women surveyed recognise that sanitary pads are harmful for the environment and 80% of them expressed willingness to shift to eco-friendly substitutes.

“Adoption of eco-friendly alternatives is a welcome move and we do see the shift happening across verticals of users,” said Jaydeep Mandal, founder and managing director of Aakar Innovations, a social enterprise that produces ‘compostable’ sanitary pads. “Besides awareness about menstrual hygiene, the change can be attributed largely to financial independence and most importantly climate consciousness.”

“Once discarded, biodegradable plastic breaks down into micro bio-plastic and remains in the soil for an unknown lifetime. So far, there are no techniques for testing and extracting micro-bioplastics from soil,” Malik added.

While different stakeholders have varied viewpoints on products, they do agree on the environmental side-effects and emphasise the need for a robust waste management system. This is a point Unicef emphasises too. “A waste management chain needs to be in place from on-point to endpoint. As cultural beliefs and stigma influence individual disposal, users must change their disposal behaviour and reduce environmental impact, pollution of sanitation systems including water bodies in rural India.”

This article was first posted on The Third Pole.

This work is under Creative Commons’ Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 England & Wales License.