All you need to know about the CAMPA Act

- A legislation meant to ensure that India’s forests aren’t completely destroyed in the name of development has environmentalists and Adivasi activists up in arms against it. Here’s why.

Suchitra is an independent journalist working on social justice with…

India’s forests have been mired in controversy since time immemorial, with corporate interests, government negligence and mismanagement often leaving forest-dwelling communities — and the forests themselves — to deal with and suffer from the consequences.

To mitigate the problem, in 2001, the Supreme Court of India ordered for the establishment of a Compensatory Afforestation Fund, and a Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA). The CAMPA came into being in 2006, and the government passed the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act, also known as the CAMPA Act, in 2016.

What does CAMPA do?

Whenever trees in a forest are felled (or “diverted”, in official speak) for non-forest purposes, it is mandatory under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, that an equivalent area of non-forest land has to be taken up for compensatory afforestation. While the responsibility to carry out afforestation falls to the state (or union territory) government, the funds for this are collected from the user agency (usually a private entity) that is developing the land.

The amount of money to be paid is decided based on a number of factors, including the goods and services — like timber, firewood, soil conservation or seed dispersal — that the forest would have provided over a period of 50 years had it still been in existence. This value is called the Net Present Value (NPV), and is calculated by an expert committee. This final amount paid by the user agency includes the NPV cost, and afforestation and a few other charges.

It is the CAMPA’s job to administer the funds and use them for their designated purpose, that is afforestation.

Why is this problematic?

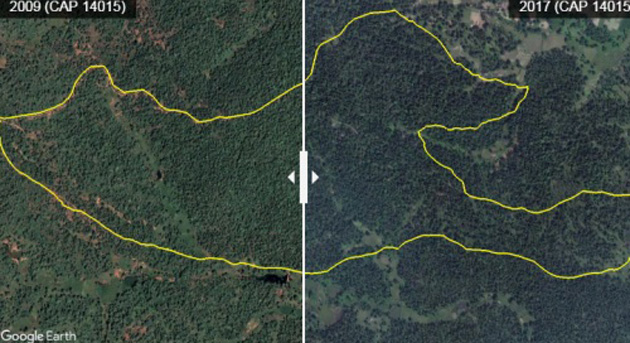

There are multiple questions that have arisen in the matter of the CAMPA Act. Questions such as why the promised afforestation didn’t happen in some cases, and questions about where the funds are being utilised. For instance, audits found that some of the money was being used in Chhattisgarh for non-forestry purposes. However, the strangest are the questions about the manner in which the planned afforestation has taken place, and the resources and opportunities lost.

After the Forest Rights Act was passed in 2006, the first claim to utilise and manage the forests was given to the people who have lived there for successive generations and whose life, livelihoods and community is woven around forest resources. Adivasi communities have not only been granted rights for the use of forest land but also for their protection and governance. The Act also dismisses the rights given to forest dwelling communities under The Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996, also known as PESA.

Since there is a shortage of available land for compensatory afforestation, many ground studies highlight that new plantations are occurring on podu (shifting cultivation) lands, or on forests claimed by forest dwelling groups under the FRA without their permission. This is having a detrimental effect on local food safety and livelihoods.

The compensatory afforestation also often happens on lands on which forest-dwelling communities depend for their livelihood. Adivasi women often make eco-friendly products like siali leaf plates, etc; and this is how they are financially autonomous, and this act completely negates the way adivasi communities survive, because in case compensatory afforestation does happen on these lands, plantations would not be of the same tree that was taken away.

Laichi Bai, a resident of Mandla District in Madhya Pradesh, has been protesting against the CAMPA Act since the last two years. The source of her woes is the Mohgaon project in Nainpur, for which native tree species such as saja (Terminalia tomentosa) and harra (Terminalia chebula) have been chopped to make way for tree species like eucalyptus and teak. She says, “We need our native trees for our livelihood as well as to prepare our traditional medicines. Now, our way of life is severely disrupted because of this, and forest department officials often harass Adivasis when we try to access the forests.”

A second example is that of Telangana’s Nalgonda District, where swathes of forest have been diverted for the Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project. Here, some of the land intended for the compensatory afforestation is barren and rugged. In such areas, afforestation means blasting rocks, importing dirt and soil, and then planting hardy species like ficus and neem that can withstand the terrain. This means that a lot of the native species that exist never get replanted, and over the years, many such indigenous plants have been pretty much entirely wiped out.

The way forward

- The state needs to ensure that the forest bureaucracy is, from time to time, oriented to understand and realise that their position as civil servants must be subordinate to the gram sabha obligation that regulates forest resources. Anything other than that will be harmful to all the legislation and public services, and will act as a hurdle to grassroots democracy being implemented.

- The state needs to consider what kind of plantations are being made, and where the compensatory afforestation funds are being implemented. This decision should ideally be made by Adivasis, who share a better relationship with the forests and are directly dependent on them.

- The provisions of acts like the Forest Rights Act and PESA Act must not be ignored by the state, and it has to be ensured that the land redirected for the developer’s perusal is not located in a scheduled tribal area such as podu lands. Pastoral and Particularly Vulnerable Tribes must become active leaders in forest planning, and not just be bystanders.

Suchitra is an independent journalist working on social justice with a specific focus on gender justice. Reading, smashing gender norms and stationery gets her very excited!