Climate crisis set to treble migration in South Asia by 2050

- The number of people displaced by climate change impacts is projected to rise exponentially in South Asia unless stronger action is taken to reduce distress migration.

Millions of people are migrating or are being displaced in South Asia due to disasters brought on by climate change, and the number could rise three-fold in 30 years unless countries in the region take strong measures to mitigate the worst effects of global warming, a report said today.

More than 62.9 million people in South Asian nations — more than the entire population of Italy — will be forced to migrate from their homes due to climate disasters by 2050, said Costs of Climate Inaction: Displacement and Distress Migration.

The report was released on December 18, observed as the International Migrants Day by the United Nations.

Failure to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, as agreed upon in the 2015 Paris climate pact, is already driving 18 million climate refugees worldwide from their homes in 2020, the report said. Conservative predictions show that forced migration will treble in South Asia alone, a region badly affected by climate change-induced disasters such as more frequent and more severe floods, droughts and cyclones, new research showed.

The report by non-profit ActionAid International and Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) upwardly revised projections made in a 2018 World Bank study — Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration — that had said there could be nearly 40 million climate migrants in South Asia by 2050.

“A combination of environmentally sensitive livelihoods, population growth and urbanisation will make South Asia one of the most active regions in terms of climate-induced migration,” said Bryan Jones, assistant professor at Baruch College of the City University of New York. “Additionally, because many of the largest and most important urban centres in the region lie in particularly vulnerable coastal areas, it is imperative that policymakers prepare for the likely influx of migrants.”

Jones, one of the co-authors of the 2018 Groundswell report, conducted research for the latest report, which said that climate change is either directly displacing people or accentuating hardship that results in distress migration.

Slow-onset impacts

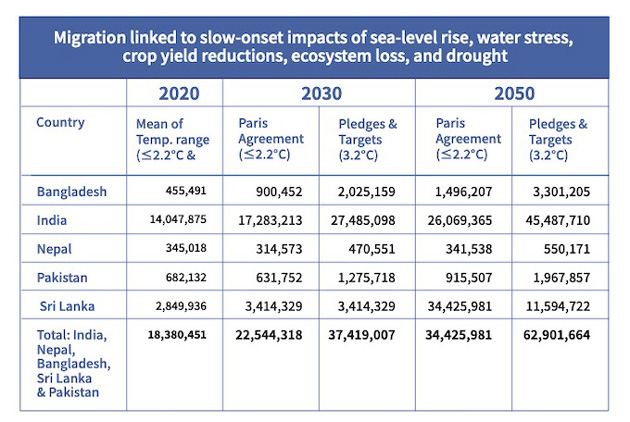

Migration linked to slow-onset climate impacts such as sea-level rise, water stress, crop yield reductions, ecosystem loss and drought in Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Pakistan could rise to 37.4 million by 2030 and as much as 62.9 million every year by 2050 if countries do not improve the pledges they made in the Paris agreement. Current pledges by 195 national governments is forecast to lead to a 3.2 degrees Celsius rise in average global temperature, far higher than the two-degree ceiling.

The number of migrants can be brought down significantly to 22.5 million by 2030 and 34.4 million by 2050 if even these five countries bring their targets to limit temperature increase to 2.2 degrees, the new research showed.

“These numbers do not include counting of those who are likely to be displaced by sudden onset climate disasters such as flooding and cyclones, to which South Asia is particularly vulnerable,” the report said. “These numbers also assume that countries will start taking action towards meeting their pledges and targets.”

South Asia recorded 9.5 million new displacements due to disasters in 2019, the highest since 2012, according to the 2020 Global Report on Internal Displacement. Floods triggered by the monsoon in India and Bangladesh and Cyclones Fani and Bulbul were among the extreme weather events that forced most people to flee their homes last year.

As local coping mechanisms fail, people are forced to migrate to survive and make an alternative living to feed their families, said a policy brief by Actioinaid International titled Climate Migrants Pushed to the Brink.

“Climate change is increasingly forcing people to flee their homes in search of safety and new means to provide for their families,” said Harjeet Singh, global climate lead at ActionAid.

The new report has demanded strong leadership and ambition from developed countries to cut emissions and support for developing countries to adapt to climate change and recover from climate disasters. It also recommended a holistic approach that places the onus on rich countries to provide support and urged developing countries to scale up efforts to protect people from climate impacts.

“South Asian leaders must join forces and prepare plans for the protection of displaced people,” said Sanjay Vashist, director, CANSA. “They must step up and invest in universal and effective social protection measures, resilience plans and green infrastructure to respond to the climate crisis and help those who have been forced to move.”

Intensifying climate migration in South Asia is not only a humanitarian crisis, but also a regional stability risk, according to the Wilson Center. Growing rural-to-urban migration will place added burdens on already-overcrowded cities to provide food, shelter and jobs, the US-based think tank said.

This article first appeared on India Climate Dialogue.