Mining industry releases first standard to improve safety of waste storage

- On Aug. 5, spurred by a deadly Brazilian dam disaster in early 2019, a partnership between the U.N. and industry leaders released new guidance for companies to manage their mining waste safely.

- The Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management “strives to achieve … zero harm to people and the environment with zero tolerance for human fatality,” according to its preamble.

- However, some environmental and human rights groups say the measures in the standard don’t go far enough.

Spurred by a deadly Brazilian dam disaster in early 2019, a partnership between the U.N. and industry leaders has released new guidance on managing mining waste.

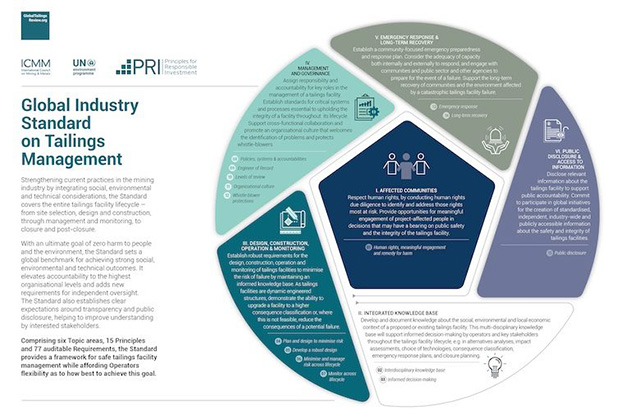

Released Aug. 5, the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management is a first-of-its-kind industry initiative to establish a benchmark for the safe disposal of mine waste, called tailings. Metal concentrations are often only a small fraction of ore, and mines can produce tailings that are orders of magnitude greater in volume than the metals they target. The most common way to manage tailings is to store them behind dams, and these have proven vulnerable to occasional but catastrophic failures.

The new standard “strives to achieve … zero harm to people and the environment with zero tolerance for human fatality,” according to its preamble. It strengthens current practices in tailings management by encouraging the industry to publicly monitor its tailings dams, to prepare for potential disasters and recovery with local communities, and to support the creation of an independent review body. Additionally, companies should employ a tailings engineer who is accountable for the integrity of dams.

“I now call on all mining companies, governments and investors to use the Standard and to continue to work together to improve the safety of tailings facilities globally,” Bruno Oberle said in a press release announcing the standard. Oberle chairs the Global Tailings Review, the body that released the standard.

The Global Tailings Review was convened by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the industry association International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) and the investor advising initiative Principles for Responsible Investment. The ICMM includes companies like U.S.-based bauxite leader Alcoa and copper and gold miner Freeport-McMoRan, and Switzerland-based industry giant Glencore. The new standard is not binding, but its creators expect industry players to implement it and regulatory authorities to use it to enforce environmental safety.

Despite the widespread use of tailings dams, there is no comprehensive database of their locations and risk factors. By some estimates, anywhere from 12,000 to 30,000 tailings dams exist, and many are believed to be structurally insecure.

“The Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management is an important milestone towards the ambition of zero harm to people and the environment from tailings facilities,” Ligia Noronha, the director of UNEP’s economy division, said in the press release.

“Its impact will depend upon its uptake and UNEP will continue to be engaged in its rollout.”

Tailings dams took the spotlight in January 2019, when one at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine owned by Brazilian miner Vale in Brumadinho, Brazil, broke and released millions of cubic meters of waste. The liquid sludge plowed 8 kilometers (5 miles) downhill, over farmland and communities. In the aftermath, authorities identified 259 people killed, but 11 remain missing. Scientists have called the Brumadinho collapse one of Brazil’s worst environmental disasters and deadliest industrial accidents.

‘At present, it falls short’

In creating the new standard, the ICMM collected feedback from an advisory body comprised of technical experts and civil society groups. Some members now say the new standard doesn’t go far enough.

“The trend in increasingly severe and frequent tailings dam failures is the unfortunate result of allowing mining companies to sacrifice safety to cut costs, dodge upfront financial obligations, and pass the buck on accountability,” Payal Sampat, mining program director at the U.S.-based nonprofit Earthworks and a member of the standard’s advisory board, said in a statement responding to the standard’s release.

“We were looking to the Global Standard for these safeguards, but at present, it falls short of what is needed,” Sampat said.

Civil society groups including Earthworks pushed for rules to hold top executives responsible for tailings dam failures, rather than lower-level staff who could be made to shoulder responsibility in the event of a disaster.

“That avoids the ‘fall guy’ or scapegoat, where you can fire that one person, but in fact nothing has really changed in the organization,” Sampat told Mongabay. The standard requires that companies appoint a “site-specific responsible tailings facility engineer.”

The groups also pushed for the new standard to ban “upstream” tailings dams similar to the one at Brumadinho, which are considered the most prone to crumbling because the dam wall is built uphill, into tailings that are already deposited. Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Peru have banned the construction of new upstream tailings dams, and ordered the phasing-out of existing ones.

“None of these are outside the capabilities of mining companies, but they have not had their feet held to the fire,” Sampat said.

The standard includes no mechanism to induce companies to decommission their upstream tailings dams or avoid building new ones. Instead, it recommends that companies regularly monitor their dams.

Bruno Milanez, a professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora in Minas Gerais, near Brumadinho, joined the advisory board midway through the consultation process. He teaches about corporate social responsibility and environmental standards and has been studying mining conflicts in Brazil since 2006.

He was skeptical about joining, he said. “These standards frequently have very little effectiveness,” Milanez said. “They create a lot of work for companies but produce limited concrete results.”

In the end, he said, he wasn’t sure whether the advisory group impacted final decisions. In addition to allowing companies to build upstream tailings dams despite some advisory group members’ objections, Milanez said the standard included no instruments to prevent conflicts of interest with auditing companies.

Dangerous dams

Tailings dam failures have occurred long before the Brumadinho disaster, and guidelines to improve their safety have been published before. In 2017, a UNEP report found that “although the number of dam failures has declined over many years, the number of serious failures has increased.”

In 2015, the Fundão tailings dam in Mariana, Brazil, owned by Vale and Anglo-Australian company BHP Billiton, burst and killed 19 people. In 2014, the Canadian province of British Columbia convened an expert panel after the Mount Polley mine released 25 million cubic meters (almost 33 million cubic yards) of waste and water into nearby lakes. Neither the mine nor ICMM adopted the panel’s safety recommendations, according to Sampat.

Last year, the Church of England, whose pension funds invest heavily in mining projects, led a group of investors controlling $13 trillion in assets to request 726 mining companies disclose their tailings dam risks. Since then, 108 companies representing almost two-thirds of the industry’s market capitalization have publicly disclosed whether they have tailings dams.

In December, 2019, a Reuters investigation with the Church of England into the disclosures found that companies have built more tailings dams in the last decade than in any previous decade. A third of the dams disclosed at the time were “at high risk of causing catastrophic damage to nearby communities” in the event of collapse, the investigation found.

An alternative standard

In June, before the new standard’s release, a report endorsed by 142 NGOs and technical specialists said the Brumadinho disaster “should not have come as a surprise.”

The report outlines its own standard of tailings management, informally called the People’s Standard. It stipulates that the safest tailings facility is the one not built. It calls for the creation of an international agency to share up-to-date information on tailings dams with the communities they affect.

“The tech and best practices are there,” said Jan Morrill, a tailings campaigner with Earthworks and a co-author of the report. “It’s just the will of the companies to invest in those technologies.”

The People’s Standard also acknowledges that “pushing toward mining new metals is not sustainable,” Morrill added. “We know that globally we need to be reducing our mineral consumption and create a circular economy so we’re not as dependent on mining for new metals.”

Other efforts to improve tailings management safety are afoot. In the lead-up to the release of the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management, a partnership between mining giants Rio Tinto and BHP and the University of Western Australia launched the Future Tails platform that promotes training in the best available technologies for tailings management and facilities. In July, several universities in the U.S. announced collaborative research centers to study and provide training in best practices in tailings management.

Other tailings disposal strategies besides dams include manufacturing construction material from nontoxic waste, storing tailings underground, and backfilling, which returns neutralized tailings to the mined hole. Controversially, some 16 mines around the world dump their waste into the deep ocean, a practice scientists say may harm marine ecosystems.

“This is not about fixing one problem only to have another pop up somewhere else,” Sampat said. “This is definitely a broader systemic question. How much are we mining? Are we mining lower ores that create more amounts of waste? Are we creating more toxic chemicals that need to be neutralized and removed from ecosystems and people?”

This article first appeared on Mongabay.